Electric guitar songs chords

You will find basically three schools of thought on songwriting. Initially you've got those that think that “either you have got it or perhaps you don’t.” Put differently, songwriters are produced, maybe not made. Others sign up to the quasi-mystical thought that every tracks have now been written as they are out there within the ether, one simply must be available to getting all of them.

Eventually, you’ve got those that consider songwriting as an art, along with its very own collection of rules and methods that even the typical musician can discover.

Although it would-be presumptuous to ascertain that anyone college is right, we'll explore the concept that songwriting, like basketball, drawing and skeet shooting, can be taught.

Needless to say, in the same way practicing a jump chance does not guarantee admission towards the NBA, no level of information on songwriting are able to turn some body into Paul McCartney, or Paul Stanley, for that matter. The idea is a knowledge of songwriting basics shall help you come that much nearer to completely realizing whatever “talent” you had been endowed with by God or fate.

Chords and Spark

Regardless if a person had been to restrict himself to a study of pop songwriting over the last 40 many years, a real instructional “guide” would use many volumes, because would involve a serious research of music concept. Our aim here's to prove a sampling of common chord progressions that you can use with your own personal songs, and analyze some of the things a guitarist can perform to add slightly zip to their songs.

All preferred tunes, irrespective of category, derive from chord progressions. Although a tune consists mostly of single-note riffs (Led Zeppelin’s “Black Dog” is an excellent example) or an a capella singing line (Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner” comes to mind), chords and general balance are suggested or alluded to by the melody. Understanding chords, as well as the way they relate to both, is essentially the building blocks of pop music songwriting.

Within journeys, you’ve undoubtedly encountered chords and chord progressions explained in numerical terms, perhaps a musician informing a band mate to “move into five chord” or a blues record talking about a “I-IV-V” pattern.

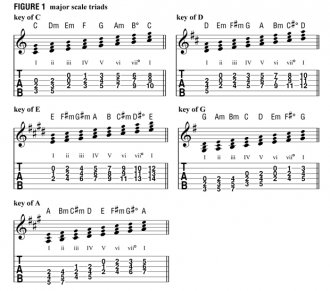

The terminology in both instances is explained in FIGURE 1, which illustrates triads (three-note chord voicings) built on major scales within the guitar friendly keys of C, D, E, G and A. The Roman numerals included under the chords suggest scale levels; those in uppercase represent major tonalities, while those who work in lowercase signify the small (the vii is diminished).

In the 1st bar of figure, C is the I (“one”) chord, making F—the fourth degree of the scale—its matching IV (“four”) chord. Consequently, a I-IV-V development in this key will be C-F-G. To look for the I-IV-V within the various other tips illustrated in FIGURE 1, just reproduce the approach we took in C.

To provide you with a feel for a design that features minor chords, let’s just take a short glance at the I-vi-ii-V development, a series that pops up in countless pop and rock songs. Within the secret of D, as illustrated in FIGURE 1, the chords will be D-Bm-Em-A. Once again, reference the figure to determine this development when you look at the various other keys.

Now let’s have a look at some common pop music chord progressions and examples of well-known tracks by which they look. As an aspiring songwriter, familiarizing yourself with one of these progressions should show invaluable to you.

Four-chord Progressions

You couldn’t switch on radio stations when you look at the 1950s and prevent hearing the I-vi-IV-V progression in any number of tracks. Therefore don’t have to be a 65-year-old doo wop lover whom bursts into rips during the mere reference to “within the However of this evening” or “Earth Angel” to be familiar with the l-vi-IV-V. Consider Hoobastank’s “The Reason” (key of E: E-C#m-A-B) and you’ll notice a prime example of this development.

Most of U2’s “With or Without You” is a I-V-vi-IV development into the key of D (D-A-Bm-G). The Beatles’ timeless “Let It Be” (key of C: C-G-Am-F) can also be largely considering this sequence.

Boston scored huge using the vi-IV-I-V development in “Peace of Mind” (key of E: C#m-A-E-B), as performed Avril Lavigne more than twenty years later inside choruses of her mega-hit “Complicated’ (key of F: Dm-Bb-F-C).

Three-chord Progressions

I-V-IV and I-IV-V progression are likely the most basic in pop music music, both are used many times that also audience which don’t know a IV chord from a foreskin recognize all of them intuitively.

Certainly one of Pearl Jam’s biggest hits, “Yellow Ledbetter, ” is dependent upon the I-V-IV sequence within the secret of E (E-B-A); “Twist and Shout, ” an enormous hit for the Beatles, is simply a I-IV-V in D (D-G-A) various other significant tracks constructed on these progressions are the Who’s “Baba O’Riley, ” (key of F: F-C-Bb), Pete Townshend’s “Let our Love open up the Door” (key of C) and semi-contemporary hits like Fountains of Wayne’s “Stacy’s Mom” (key of E: E-A-B-A).

What do Jackson Browne’s “These Days, ” Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mr. Bojangles, ” Paul Simon’s “America” and Bob Dylan’s “Don’t think hard, it is All Right” have as a common factor? Each is based to some extent on the I-V-vi-I-IV progression, a sequence that stays preferred among singer-songwriters.

One likely reason behind its enduring appeal is the fact that, when played in the secret of C (C-G-Am-C-F), it fits—and there’s truly no better way of saying this—just close to the fretboard.

In addition “just right” in C is I-VI-II-V-I (C-A7-D7-G7-C), a progression that was originally popularized by ragtime players a lot more than 100 years ago and seems this kind of modern-day hits as John Sebastian’s “Daydream” and Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant.”

The i-VII-VI is familiar to anyone who understands the outro part to Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” (key of a small: Am-G-F). Adding another VII chord to the three-chord progression gives you Jimi Hendrix’s form of “All Along the Watchtower” (key of C# minor: C#m-B-A-B) and chorus of Aerosmith’s “Dream On” (key of F minor: Fm-Eb-Db-Eb).

The I-bVII-IV (key of of C: C-Bb-F) features the “flat-seven” chord. This development appears in countless songs, included in this Lynyrd Skynrd’s “Sweet Residence Alabama” (key of D: D-C-G) and a variety of AC/DC tracks, including “Back in Black” (key of A: A-G-D).

When you’re simply starting out as a songwriter, go ahead and borrow the chord progressions cited above—just take care to not ever additionally borrow the melodies. George Harrison made this blunder when he wrote “My Sweet Lord” and finished up paying out the composers of “He’s So good” a not-so-sweet bundle of money.